Certainly in a PH crack repair one would not wish to remove any (more) chimney depth from an embouchure whose wooden walls are already about 1/3 shallower than “normal” heads because of the double metal liner and cut-out in the inner one which provides a window for the the hole to move along as the mechanism telescopes. In normal, single-lined heads, I don’t think the loss of chimney depth even with a concentric re-bore is necessarily all that much or that serious.

Of course, much depends on just how much the wood has shrunk and so how much bore enlargement is needed. I think a case-by-case assessment would be needed. Most of the “normal” heads I have fixed cracks on have not needed all that much bore enlargement to readmit the liner tube. I don’t have a lathe, so I have to do it with files/dowel and sandpaper, and I do try to do it eccentrically, away from the embouchure, but I don’t think I have yet noticeably-to-the-eye ovalised (Jon can keep his eggs!  ) a head bore, nor lost as much as the thickness of the liner tube wall in the depth of an embouchure.

) a head bore, nor lost as much as the thickness of the liner tube wall in the depth of an embouchure.

I can’t see much point in trying to rehydrate the wood - any restoration of its original volume and configurations by such forced methods would inevitably be temporary and not conducive to or contributory towards a stable outcome. That said, I have found steam useful as a reforming method where a cracked wooden part had become seriously distorted, such that one could not simply close the crack up - neither force it fully back together nor get its edges aligned correctly! (See this photo album.) I was amazed how well and readily the cocus responded to steam!

As for maintenance lubrication of a PH:

David, sometimes (as I accidentally found once, to my initial dismay as you may imagine!) it may be possible to partially disassemble a PH without needing to remove those screws you mention or the lynch pin - certainly sufficiently to apply a decent sealing lubricant between the tubes. My own PH did this to me! I have since done it deliberately several times when it started to leak air between the tubes or around the stopper. I’ve just done it again to take some photos for this thread. I should emphasise there is nothing broken in my PH (barrel cracks only) and the only thing missing is the original silver face-plate, which would have been soft-soldered onto the traveller. Paul Davies’ replacement is simply push-held in place with beeswax (one would have to renew the cork lapping if one tried to solder it onto the traveller).

First nearly fully extend the tuning mechanism - wind it out until it stops, then take it back a few turns. Then insert a thick dowel with a slightly hollowed end (Paul Davies made my such a thing for inserting his replacement for the missing stopper face-plate of my PH - my flute came from him) - or maybe with a rubber pad securely stuck to it for better traction - up the head and press it against the stopper, then screw it around (anticlockwise looking from the barrel end), trying by friction to screw the stopper off the end of the mechanism’s spindle. There is no limiter holding it on. Screw the stopper around, then gently extend the slide by the adjuster crown and see if it will screw right off - this may take several goes.

If the stopper will screw off (it may not), you can then keep screwing the cap and drive the inner tube (it has brass disc screwed into its top end with a threaded hole in it) right off the spindle. You’ll feel when it comes free. Then gently draw the tubes apart (be careful not to twist at all!) and you can use a probe through the thread hole at the top to remove the travelling stopper if you wish. The outer tube will remain fixed within the wooden sleeve, of course. You can then clean the tubes’ contact surfaces and the stopper’s cork lapping, re-grease all and carefully reassemble.

To reassemble, replace the stopper inside the inner tub, then carefully introduce that back into the head, being especially careful when it is most of the way in to line up the locator/guide lug into its slot. Push the tube in until its end-block reaches the spindle, then screw the crown to draw the inner back onto the spindle. Draw it right in until the tuning slide is completely closed, then use your dowel to press and screw the stopper back onto the spindle as far as it will go. Wind the mechanism back to fully open and see if it stops/self-limits or starts to come apart again. It should not come off the spindle at full slide extension unless the stopper has screwed/worked itself outwards along it in the course of use - which is what had happened to mine when it first fell apart! If it does come apart, get it back together as before, then, after screwing the stopper fully home with the slide closed, open the slide a little and screw the stopper a bit more. Now check if the extension is limited, and also that the slide can be fully closed.

This operation lets you get a sealant/lubricant everywhere necessary to restore a good seal between the tubes and between stopper and tube (you can even renew the cork lapping if need be), but it doesn’t let you get at the inner workings of the head screw mechanism, should they need any attention (relatively unlikely).

Beyond all that, I suggest asking Chris Wilkes for his advice, though I know he may not respond if he doesn’t feel like it. He has repaired quite a few PHs (including crack repairs) to my knowledge, and has had mine fully and properly apart.

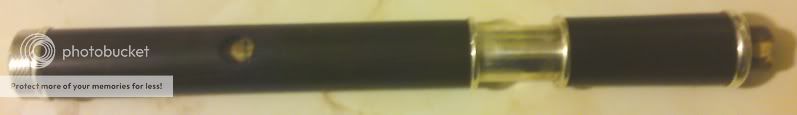

Here are the photos of what I just did to my PH. I’m afraid they had to be done under not very good artificial light, so are not the best! Apologies…

The head disassembed in the manner I described above, with the only tools used - the dowel to “unscrew” the stopper and the skewer to probe through the top thread-hole to push the stopper out.

The stopper/traveller, “short” side (the central bulkhead with the threaded hole through it for the spindle is not placed centrally within the length of the tube, more about a 1/3-2/3 split).

The stopper/traveller, “long” side

Note that the silver faceplate should be soldered to one end, usually the “short” side, I believe. Because mine lost its plate and the replacement is not soldered on, it is easier to do these stages with it removed and to press it back on as the last step of reassembly.

Reinserting the stopper into the inner tube

The stopper pushed home to the end of the inner tube (face plate still off)

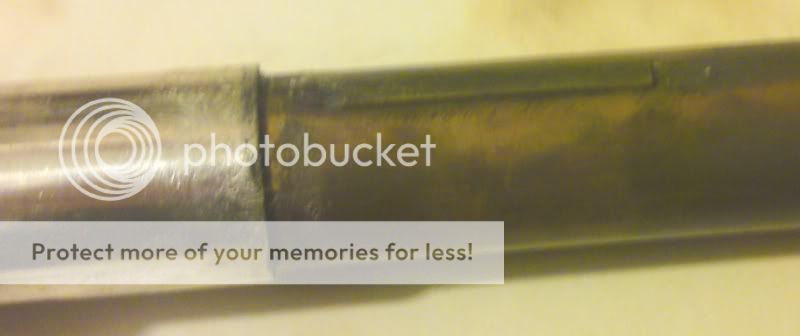

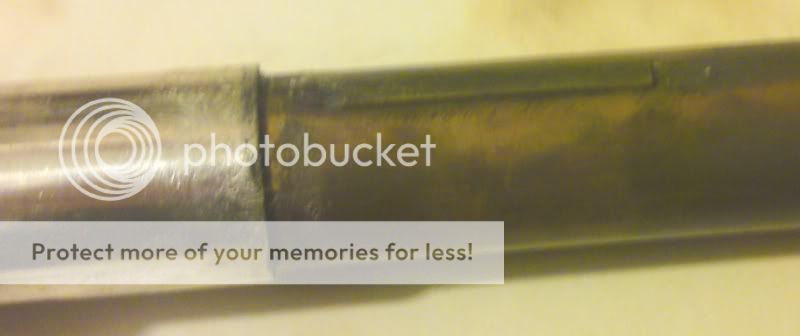

The locator/guide lug on the inner tube. This is what gets damaged/ripped off/mangles the tube if someone tries to twist the head and barrel of a PH like an ordinary head!

The locator/guide slot in the outer tube, within the head/wooden sleeve

View into the head (outer tube and sleeve before reinserting inner tube) showing the screw spindle at the top

Reinserting the inner tube into the head

The head reassembled, stopper screwed right home, face plate replaced, and then the slide opened to its maximum extension - without falling apart! - the stopper in its correct position on the spindle prevents the tubes being screwed apart.