Julia, its one of my trade secrets. I have not always been a weak flute player. Quite the opposite. I started messing with flutes at age 6, playing around with an old family Civil War era fife that I still have. All throughout grade school and high school and into college I played the silver flute, and even made it to one of the preparatory orchestras of the Portland Junior Symphony before high school graduation ended that. There were days in which I would practice from the moment I woke up to the moment I fell asleep. On sustained tone competitions - to see who was the last person playing amongst a group of flute makers, I was always the last person standing. Always. But there were way too many better flutists with nicer flutes (all Haynes, while I was struggling with my crummy big-bored Artley) for me to consider a professional carer as a symphonic player. Composing also seemed much more interesting and it remains so. Then I had a brief flute playing hiatus after college abruptly ended due to my inability to afford it.

A number of years later after involving myself in lutherie, I started making flutes and immediately for Irish music, since there was local demand for it with Jan Deweese living and teaching close by and getting the Portland Irish Music scene started, along with Artichoke Music which had a nice collection of flutes for sale including some Rudalls and Clementis, not to mention Kevin Burke and Mícheál Ó Domhnaill who arrived a little later. I was there when it started. I also had some excellent instruction and played in sessions at Lark Camp and other venues, as well as for contradances in Portland and elsewhere. The pub scene though was something I couldn’t handle due to the secondhand smoke. One hour at Murphy’s in Seattle and I would be essentially disabled for days. I am still hypersensitive to tobacco smoke, probably from growing up in it, as my parents both chain smoked.

During those years in the mid 1980s I was making Pratten copies (the originals I measured are owned by Mickie Zekley) and the west coast term for my flutes was “Honker”, nicknamed by Richard Cook who taught us at Lark Camp. I was playing a bunch of flute then and got a big tone out of my instruments and wanted to keep getting that big tone out of my instruments.

But then I got distracted by bagpipes and other types of music. French bagpipes, Spanish, Uilleann, Northumbrian, Swedish, Breton, Dudelsacks, Lowland, Scottish Small Pipes, Union Pipes. And then there were Bombardes and other noisy instruments. I am still distracted by these, especially the Galician Gaita which I do play regularly and increasingly. Then reed making and I was one of the “yogurt reed” pioneers. Meanwhile all the Irish sessions where I lived were just too dangerous smoke-wise so I avoided them like the plague. I got out of the habit of playing the flute recreationally totally and confined my flute playing to the workshop, only during tuning and voicing and testing. At one point I was living with another full time musician and she occasionally gave me a hard time saying that I should practice all the time and be out trying to play as much music on the flute as possible, if I wanted to consider myself a legitimate flute maker. Instead I was retreating into my workshop and feeling bad about myself for not being out playing so much. I grew sort of reluctantly content with the idea of “performing with my lathe” and avoiding the stage.

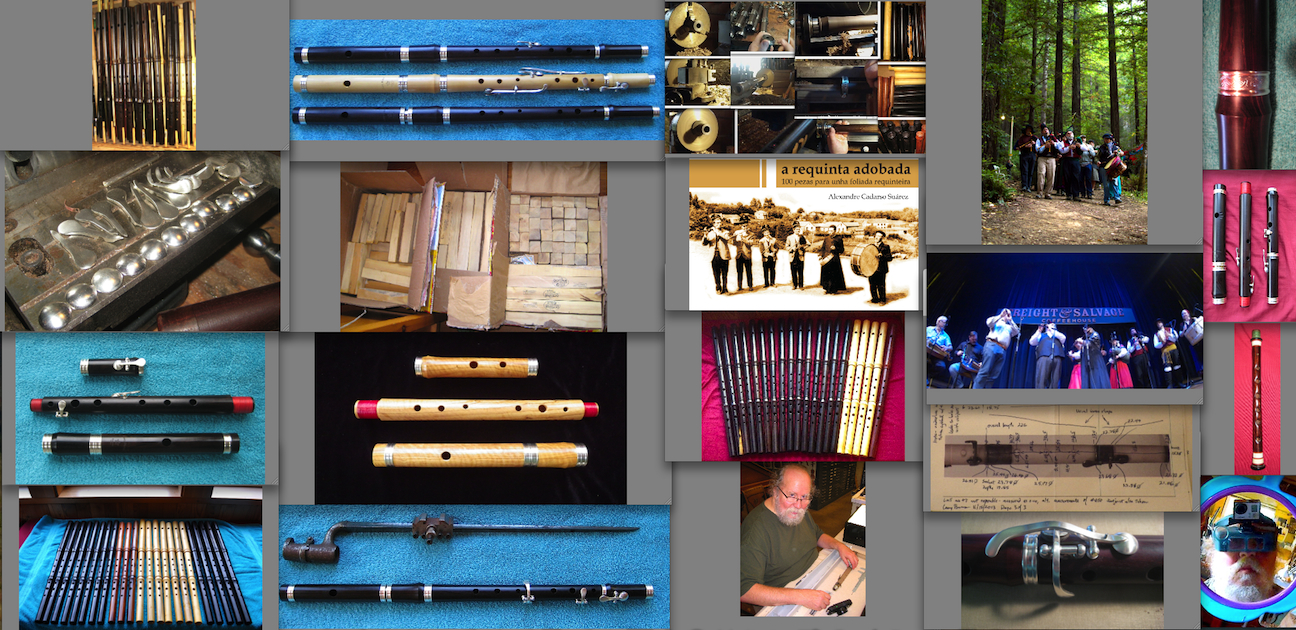

In the workshop however, I always stuck to what the flutes should feel like to the player and sound like as well, etc.. What I didn’t realize until about a decade or more later is that as my embouchure weakened from this lack of regular playing and practicing, that I was iteratively forcing my instruments to do all the heavy lifting to create this big tone and pleasant response and feel, which I still wanted and could understand. This can only happen when one tunes and voices several flutes a year and my output has always been around 100 flutes a year minimum. (This year the number is currently 186 but I have two other flutes finished (one is a Mopane Standard Folk Flute that isn’t spoken for - let me know if anyone is interested) and I have a number of factory second flutes that I am donating to a Galician Music school in Spain. This year my output of flutes sent out into the world may just hit 200 for the first time).

This is also possible when one has that fore-knowledge of what a well playing flute should feel like, and how big a tone sounds, etc. I can still get a big tone on a crummy flute if its capable of a big tone, but not for long before my embouchure entirely poops out. So I have that muscle memory (similar to how this 58 year old has the memory of being able to ride bicycle 100 miles a day over mountain passes 30 years ago!) - just not the muscle strength to do it very long. However, this has guided my flute design by feel and the result is that my flutes end up being very forgiving to a beginning player - and these players make up the bulk of my business. These flutes also end up working very well in the hands of a capable player. Thus my flutes span the range of people who have never played a flute before to such players as Grey Larsen, John Skelton and Matt Molloy regularly playing on my low flutes in Bb and A - all guided by the same tuning and voicing principles and practice.

This practice also requires never allowing one’s flute design to fossilize into something unvarying, as far as embouchures go. I don’t stick to the 7 degree standard that Rockstro described of Rudall flutes in the 19th century - but I have seen several flutes by modern makers with pretty much the same embouchures as the Rudall and Pratten originals. These still work for those flutes and play well if done well. But my flutes have their own unique bore profiles and even these haven’t settled. Other criteria such as making the flute easier for smaller hands has driven my design some through years of trial and error. I am about to rework the entire bore design on my Standard models, mostly due to the fact that my current reamers have about had it and are on their last legs. Its an opportunity to address some 3rd octave tuning issues (my smaller handed flutes don’t produce a very nice high E in the 3rd octave, which is usually not a problem in Irish Music - but is sometimes if one wants to play jazz). The nice thing about making several flutes a year (the majority of which are my inexpensive Folk Flutes which are acoustically the same design as my expensive ones) is that it gives me lots of opportunity to innovate and practice and experiment. It keeps my tuning and voicing skills in shape. Every flute is essentially a prototype for the next. I like the fact that my design is constantly evolving.

I know this may seemed counterintuitive. This has been my experience. I know that I want to get a big sound out of my flutes. I just don’t want to have to work hard to get it. Having a flute that plays so easily out in the market results in a happy clientele and helps to keep me in business.

I gotta go wrap presents for the family now that everyone (well, just Nancy. Our daughter Lila flies in tomorrow) is in bed.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year!

Casey